When we made the decision to sell our company, it was based on market timing as opposed to the more common reason a lot of entrepreneurs end up selling.

More often, I see founders sell when they are experiencing burnout, overwhelm, or scaling problems that they don’t know how to solve themselves.

I’ve always considered myself more of an investor than a purebred entrepreneur.

(This is the second installment of a three-part series. You can read the first one here, and the conclusion here.)

We started an oil and gas investment company in the midst of one of the greatest booms in history. Land prices had risen nearly 500% since we started, and our portfolio had become a very attractive asset to institutional buyers. My reasoning was that the boom was becoming long in the tooth, and there was more downside risk than upside left in the cycle.

We couldn’t have timed it better. We got our first payment in July and our second in January, when oil prices were at nearly $80/bbl. By March of that year, OPEC announced that they would be increasing supply, and prices cratered in a spectacular fashion. At one point, the spot price of crude actually went negative due to a storage supply squeeze.

Even with our fortuitous timing, it was hard to let go of the company and brand that we had built. Our marketing centered on our brand story of military service, and my business partner and I were very much the face of the brand.

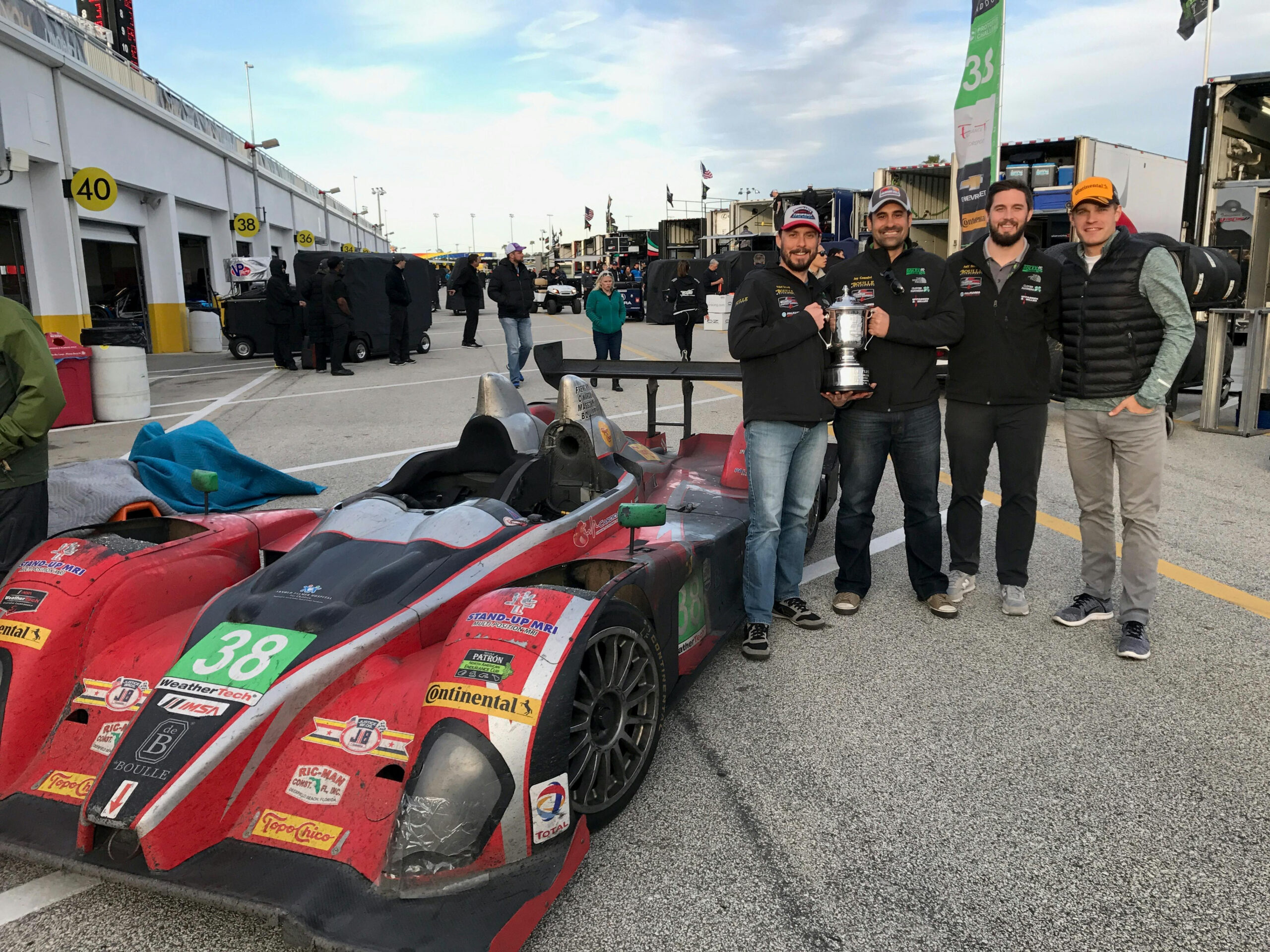

I loved my company. As a boutique firm, we were a small, close-knit shop. I founded the company with my best friend from the Navy, and we had hired my two brothers a couple of years before. We were proud of our success, and we sponsored a local cycling team. In 2017, we even sponsored a friend’s race car, and he went on to win the Rolex Daytona 24.

It was hard giving all of that up. We said goodbye to our office and the memories we had created there and set out to figure out whatever it was that would come next.

It was during this time that I decided to start coaching entrepreneurs at the gentle prodding of my mentor, Phillip. I had been an angel investor for the better part of a decade, and I deeply enjoyed mentoring the founders of our portfolio companies.

However, I was mostly enjoying my semi-retired life. I was spending a lot of time playing with my kids, traveling the world, and embarking on various adrenaline-fueled adventures with my action-sports-addicted buddies.

By all accounts, I was living the good life.

When the wheels came off, it was due to two compounding factors. First, I was deploying my assets into illiquid investments rather than focusing on cash flow. This, in turn, created pressure to replace the income lost in the sale.

Second, after becoming curious about buying a company rather than starting another one, I decided to acquire a distressed e-commerce company.

In retrospect, acquiring a distressed company in an attempt to shore up liquidity issues is a terrible idea. However, I fell in love with the deal and underestimated how difficult it might be to turn the company’s cash flow positive—mistake number one.

To me, it seemed like a simple problem: the company was in debt and had a balloon payment approaching. Because of the debt 333service, they were unable to secure refinancing options.

My plan was to swoop in, clear the debt stack, recapitalize, and it would be off to the races.

I decided to acquire the company for the sum of its debts plus inventory. The deal came out to roughly $2.3MM, and I put up roughly 50% of the capital. To raise the balance, I called a few friends, most of whom I had done successful deals with before.

This was mistake number two. Months later, when I was hemorrhaging money and knew there was little chance of success, I held on too long in hopes of saving face with my buddies. Even though I saw the writing on the wall, my strong sense of duty to not let my friends down overrode my best judgment.

And just like that, my newfound sense of freedom was gone. Looking back, I am awestruck by how quickly it all fell apart and how a couple of seemingly innocuous decisions toppled the whole structure.

In the Navy, we call this the Swiss cheese model.

The analogy is that if you were to imagine stacking twenty slices of Swiss cheese, it would be very rare that the holes would line up perfectly so that you could see all the way through the stack. However, in some cases, over thousands of stacks, the holes would indeed line up perfectly.

We can view our decisions in the same manner. Due to redundancy and randomness, we are often safe from one or two decisions causing a critical failure. However, sometimes, a single string of bad decisions can lead to catastrophic failure, just like the holes in Swiss cheese.

Another skill set I learned in the Navy is the power of the debrief. For any given mission, we would often plan for an hour or two, fly the 90-minute mission, and then spend 3-4 hours debriefing every minute detail.

We didn’t talk about the things we did right—that was the standard. Instead, we focused on every single place that we could improve—even if it seemed microscopic. This attention to detail and commitment to excellence kept us alive in critical situations like carrier landings and close air support missions.

It was this power of debrief that allowed me to look back on this situation with objectivity and find the places where I had a breakdown in decision-making.

Through this process, I created a model to avoid such outcomes in the future, and one that I love sharing with other founders who may be contemplating an exit, now or in the future.

Stay tuned next week when I’ll break down the lessons I learned – including an actionable step-by-step guide.

In the meantime, perhaps ask yourself:

Where might the holes in the Swiss cheese might be lining up?

After all, awareness is the first step in mitigating risks.

Stay wealthy, my friends,

Mb

(To continue reading the third installment of the series, click here.)